The eternal psychological research of human beings

In the different historical moments and in the various cultures, psychotherapy has been practiced according to specific ways, different from those we use today: however, on close reflection, several factors seem to be common.

Taken into account the specific differences, today’s request for psychological or medical help reflects many different as well as similar ancient acts made by men and women of far away who would approach shamans, wizards, kings, priests, teachers, philosophers, prophets, in order to “find themselves”. The rite of what we call today a “check up”, a “consultation”, or a diagnostic/therapeutic “session”, reminds practices, ceremonials, and treatments that these therapists of yore practiced with their patients, promising to heal them or, more generally, to let them find a way out from their physical-psychological disease.

Let’s not forget the role of philosophers in old Greece, such as Socrates, Plato or Plotinus: groups of students and thinkers were used to gather around them, eager to find out the hidden truth, visible only to those who dedicated their lives to such a kind of meditation. People often asked philosophers questions about the comprehension of the world, about human life, or the meaning of existence itself: questions that psychologists know so well.

In several areas of Greece, for instance, where temples of Aesculapius (the god of medicine) were widespread. Recovery took place by means of different rituals. Among them there was “incubation”: patients were made to be laying on the ground for a whole night inside a cave. There, they had a dream or a vision that healed them. In America and in Tibet people used other healing rituals. In Guyana (South America) patients were hypnotized (this practice is still used today by some psychotherapy schools) and sometimes it happened in big groups of patients who entered a collective trance.

Rodin The thinker

Primitive medicine (today called “magic”) has been practiced all over the world, and it is still used among today’s non-industrialized populations. In some cases, wizards cause a “magical illness” which often leads patients to death in a few hours, as testified by the ritual of the cane and the bone (Central Australia, Melanesia). Sometimes, these ill-fated effects of black magic are (were) neutralized by acts of reparative magic, effected by wizards.

In ancient times, there were two therapy schools: the magical-religious and the empirical-rational ones. According to the first school, illness was the consequence of a possession by evil entities. People thought that in order to be healed (or, at least, to bring relief to the patient) it was necessary to force these entities out of the patient’s body.

Let’s mention Pythagoras (570 b.C.), philosopher and teacher of the Pythagorean school: in between philosophy and religion, the structure of this movement was based on common life and practice (moreover, open to gentle sex). As Orphism, Pythagorism was aimed at individual salvation, obtained by followers through a gradual purification (through knowledge, studying and the consequent achievement of the truth). Initiates were not allowed to eat some kinds of food (such as beans, meat of white rooster) nor to perform specific activities (as breaking bread into pieces). Pythagoreans believed in reincarnation, in soul as the “harmony of the body”, in the harmony of opposites (limited/unlimited, good/evil, lightness/darkness), in the world as a “cosmos”: to enter this sect people had to become “acusmatica” (those who could only listen to the revelation) at first, and then “mathematica” (those who were authorized to research and rationally justify the truth). This distinction can suggest many images, as the relationship psychologist/patient, teacher/disciple, professor/student. The principle of the balance obtained by the opposites (later taken by Heraclitean) reminds the “coincidence of opposites” (Jung).

Pitagora di Samo

The empirical-rational view took birth in the 18th century, in concomitance with the discovery of ‘scientific method’: what until then was called ‘therapeutic’ was severely criticized, including wizards, prophets, exorcists. Scientific medicine had risen. During that time, psychological conflicts were defined and evaluated as disorders with organic origins: people were used to think that those conditions were caused by the malfunction of a structure or an organ. Certainly Sigmund Freud was the first one who created a systematic theory of a non-organic origin of psychic disorders. But there are other two great thinkers, during the 18th century, who built the basis of psychoanalysis and psychology.

At the end of 1700, an overt conflict took place between the physician Franz Anton Mesmer and the exorcist Johann Joseph Gassner. On the one hand, there was the German Mesmer, son of Enlightenment and father of the so-called ‘animal magnetism’, who had many ideas and new techniques he staunchly trusted. On the other, there was Gassner, an Austrian countryside priest, a very well known healer, popularizer of ancient traditions still held by his contemporaries, who believed that faith in Jesus could bring patients to recovery. Around those figures gathered groups of patients (as we would call them today), coming from all over the world, hoping and believing in them and their rituals. As we can see, human beings always looked for this kind of characters, charismatic men, mysteriously therapeutic. Philosophy, science, religion were lumped together: fields not well distinguished but mixed, combined in myths, rites, beliefs, phantoms, truths.

But the Viennese world, at that time, was not ready for this kind of changes. However, Gassner had the better of Mesmer. The latter, on the other hand, sometimes compared with Cristoforo Colombus for the level of his theories, gave birth to dynamic psychiatry, the mother of today’s psychiatry and psychology. As we can see, from that primeval and blurred mix of different fields, beliefs, superstitions, traditions, have risen today’s psychology and psychotherapy.

Rites in a tribal society, early 20th century

During Romanticism, new dynamic psychiatry was born: the vision of human beings as part of nature (Naturphilosophie), the sensitivity of the ‘law of opposites’ and the concern for primordial phenomena (Urphänomene) moved the focus of researchers on concepts that will be the pillars of analytical psychology (C.G. Jung) and psychoanalysis (S. Freud). The concept of collective unconscious (Jung) and the drive dualism (Freud) are about to rise; people are again interested in the world of dreams and in its universal symbols (Von Schubert).

What kind of conclusions can we draw, after this brief diachronic view? Different considerations are possible. I think that, since the most distant ancient times, human beings needed to rely upon someone, to resort to his help, cure, listening and practical assistance. If we reflect on history, philosophy, history of philosophy, we can realize how much individuals have always needed psychology and its help. The way people asked for a psychological support was portrayed by the characteristics of the different historical periods: by bones, trance, faith, words, individuals tried to ‘appease’ this request. On the basis of this research, people have always looked for a point of reference: human beings have searched for the spiritual/living “other” because they needed comparison, or in order to find out an answer to non-understandable things, to meet their own “self”.

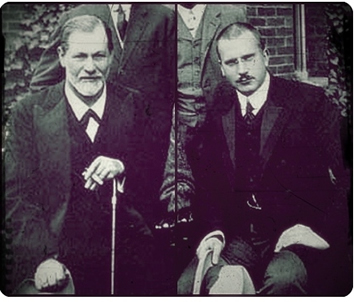

S. Freud and C.G. Jung

Beyond fashions or customs, we are now as we were once: individuals looking for a lens through which we might see the reality (that includes ourselves). There’s nothing new in this research, the eternal pursuit of our truth.

There’s a source of dissatisfaction in the human heart, from which bad mood and anxiety come out (Maori proverb).